In Praise of: Trees

Words By Caroline Gladstone

Illustrations by Matt BleasePhoto by Richard Gaston“I invite you to share with me the joy that trees can bring us.”

Peter Wohlleben, The Hidden Life of TreesTree-watching is a very under-rated hobby.

We tend to pass trees by, acknowledging them as part of the landscape, and paying more attention to wildflowers or wildlife. But once you start to recognise trees and to really observe them, they are every bit as fascinating and rewarding.

Learning to recognise trees is an open-ended process: once you can distinguish an oak from a birch or a lime, you will start to see that there are different types of oak, and that will lead you down a whole new path of exploration, which will include folklore, history and uses, some of which I have included here.

The first steps are the hardest, and so here is simple guide to identifying five of Britain’s most common trees. Once you have identified your trees, why not keep a monthly diary of observations and track how the trees change each month?

Look out for leaf buds, leaf growth, flowers, seeds, fruit, fruit fall, leaf colour changes and leaf fall.

Think about how the flowers are pollinated and how seeds and fruit get dispersed. You’ll be amazed by what you learn!

English Oak - Quercus robur

The English oak represents the very essence of the British countryside. It is the king of the broadleaved trees, whose strong, majestic and steadfast image is buried deep in our national psyche. It is also one of the longest living native trees and can span several generations.

The oldest English oak on record is Bowthorpe Oak in Lincolnshire which is over 1000 years old. The English oak is the most common tree in central and southern British broadleaved woods, and the second most common native tree in Britain. It is a large, flowering, deciduous hardwood that grows relatively slowly.

It can reach 40m, although the average is 15m-20m.

Shape:

The trunk is single. The crown is a large wide-spreading canopy of rugged branches with sturdy branches beneath.

Bark:

Brown with deep fissures that develop with age.

Leaves:

Dark green and shiny, with 4-5 deep lobes and nearly sessile (stalkless), 7-14cm long. They grow in bunches and appear in mid-May. They turn rusty yellow before falling in the autumn.

Flowers:

Long, pale yellow hanging catkins that appear in spring.

Fruit:

Acorns 2-2.5cm long with a distinctive cupule (cup-shaped base) and a long stalk. They ripen from green to brown and fall in the autumn. (An oak will only produce acorns when it is 50 years old.)

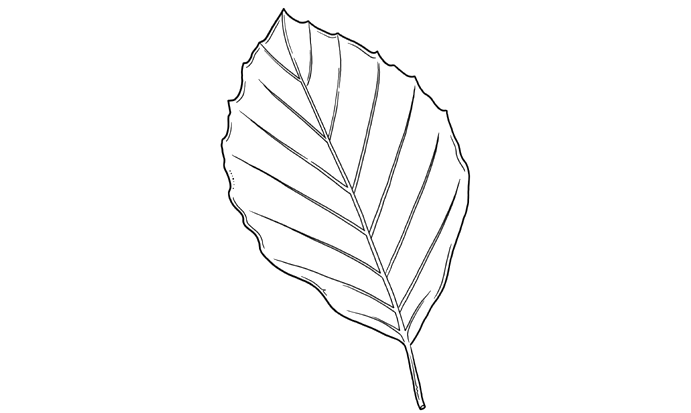

Beech - Fagus sylvatica

If the oak is the king of the broadleaved trees, the beech is the queen.

Monumental and majestic, it became popular in the 17th century, planted widely as an ornamental feature in parklands across Britain. Standing beneath the leafy canopy, its cathedral-like branches spreading upwards, is awe-inspiring.

It is also the tree you are most likely to see with ‘I luv u’ carved into the trunk, because its bark is particularly soft, but lovestruck teenagers are not the first to discover this. The word ‘book’ probably comes from the ancient English bōc, meaning beech, which was once used for writing tablets.

Mature trees can grow to upwards of 40m.

Shape:

A strong, sturdy single trunk with a huge, domed canopy.

Bark:

Smooth, thin and grey, and often has horizontal etchings.

Leaves:

Leaf buds are dark brown and shaped like a very pointy torpedo, with a distinctive criss-cross pattern. The young leaves are lime green with silky hairs. These become darker green and they lose the hairs as they mature. 4-9cm long, simple stalked, oval and pointed at the tip, with wavy edges. They turn russet in the autumn, and while some trees lose their leaves, some will keep them till spring.

Flowers:

Beech has both male and female flowers (monoecious). In April and May, the tassel-like male catkins hang from long stalks at the end of twigs, while the female flowers grow in pairs, surrounded by a cup (cupule).

Fruit:

Once the female flower is pollinated, the cup becomes woody and prickly, and encloses two beech nuts which fall in the autumn.

Larch - Larix decidua

The common, or European larch, is the only deciduous conifer native to Europe and was introduced to Britain in the 1600s as an ornamental tree.

It is synonymous with the changing seasons, heralding the arrival of spring with its vibrant lime-green shoots and deep pink flowers, and announcing the onset of winter with the soft carpet of golden needles it sheds.

Larch has been associated with Scotland since the 18th century, when several Dukes of Atholl discovered it was a fast-growing timber tree, and over 100 years, planted around 27 million trees across Perthshire (according to local folklore by firing seeds from cannons!). No Highland Games is complete without a ‘tossing the caber’ competition, and traditionally the caber is a larch pole, about 6m long and weighing about 80kg.

Mature trees grow up to 30m tall.

Shape:

Tall and conical, with a single trunk, broadening as it matures.

Bark:

Thick and pinkish-brown, developing deep fissures with age.

Leaves:

Soft, thin needles that grow in rosette-like clusters along the twigs. Bright green in the spring, darkening over the summer and turning golden yellow in the autumn before falling.

Flowers:

Look for the male flowers in round clusters of creamy-yellow anthers on the underside of shoots. Female flowers grow at the tips of shoots and are often called larch roses – flower-like clusters of scales in deep pink, green or white.

Fruit:

After pollination, the female flower ripens into a round green cone which turns brown through the autumn.

Hazel - Corylus avellane

The hazel is a small, native, deciduous tree that is usually coppiced. It is usually found in hedgerows, scrub and the understory of lowland oak, birch or ash woodland. It is one of the most useful trees because of its bendy stems.

The nuts are sweet and delicious and until the 1900s, hazels were grown in Britain for the nut harvest. Sadly, nowadays, most hazelnuts are imported.

The Celts believed that hazelnuts imparted wisdom and inspiration. One ancient tale tells of nine hazels which grew around a sacred pool. The nuts dropped into the water and were eaten by the salmon that lived in the pool. Wanting to become omniscient, a Druid teacher caught one of these sacred salmon and asked a student to cook it for him. A blister appeared on the fish skin, and the boy popped it with his thumb, which he sucked to cool it and so absorbed the fish’s wisdom. The boy was the giant Finn McCool, who went on to become one of the greatest heroes of Gaelic mythology and the builder of The Giant’s Causeway.

If left to grow, it can reach a height of 12m.

Shape:

The trunk is usually multi-stemmed. It has an even, rounded canopy.

Bark:

Smooth and grey/brown, and peels with age.

Leaves:

Simple, round to oval with double-serrate edges, hairy and soft on the underside and pointed at the tip. They are 8-10cm long and 6-8cm broad, turning yellow before falling in autumn.

Flower:

Hazels are monoecious (both male and female flowers on one tree) but the female flowers must be pollinated by pollen from a different tree. The yellow male catkins (5-12cm long) appear before the leaves and hang in clusters, from mid-February. The female flowers are tiny and mainly concealed in the buds, with only the bright red 1-3mm styles visible.

Fruit:

After pollination, the female flowers develop into oval fruits, which hang in groups of one to four. They mature into nuts with a woody shell, 1-2.5cm long and 1-2cm in diameter, partly or fully enclosed by an involucre (husk). Get them before the squirrels and dormice do!

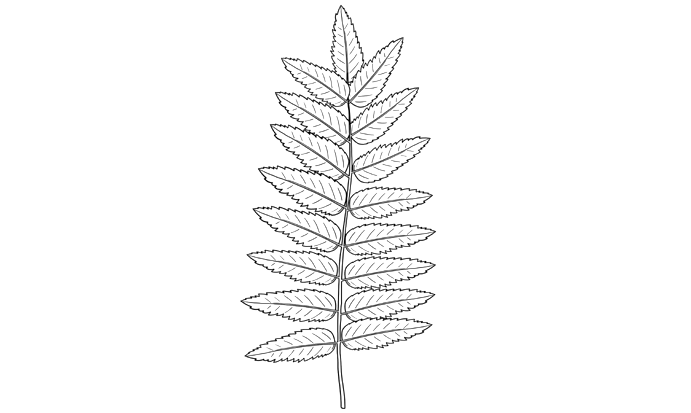

Rowan - Sorbus aucuparia

Rowan, also known as mountain ash, is a native, deciduous tree and one of the shortest-lived in a temperate climate, with an average of 80 years.

It is hardy and will grow pretty much anywhere, in a central London park or in wild, disrupted and inaccessible places, and can survive at a higher altitude than any other tree in Britain.

Its strong wood has many uses, and the rowan is also surrounded by Celtic folklore. It is said to have the power to protect and ward off witches and evil spirits, to guide travellers on long journeys, and a bumper crop of berries foretells a harsh winter ahead.

Shape:

The trunk is slender and often multiple. The branches stick out and are slanted upwards and it has a loose, roundish or irregular shaped crown.

Bark:

Smooth and slivery grey, becoming grey-black with lengthwise cracks as the tree matures.

Leaves:

Very similar to the ash, the leaves are pinnate (like a feather), usually 5-8 pairs of serrated-edged leaflets with a single leaflet at the tip. Dark green on the upper side and grey-green on the underside, turning fiery orange in the autumn before they fall. The leaf buds are purple and covered in soft white downy hair.

Flowers:

Corymbs (clusters) of yellowy-white flowers (like elderflowers but less fragrant) in the spring. Each flower has 4 tiny petals.

Fruit:

After pollination, the flowers ripen into clusters of bright scarlet to orangey-yellow berries in the autumn. If you can beat the birds to the berries, you can make a fabulous tart jelly that goes beautifully with red meat and specially game.